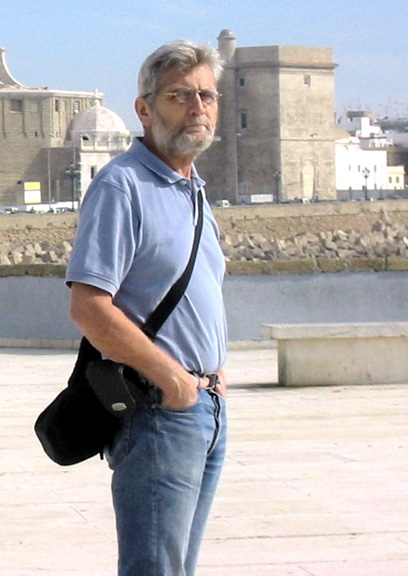

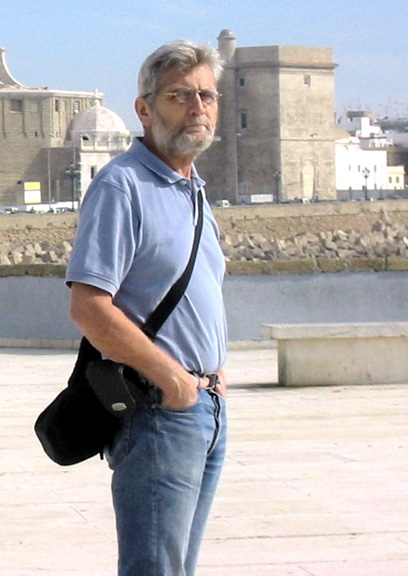

CS in Cadiz: photo: Eve Monrad

Recently Heard Concerts

Edge Festival, Berkeley, June 5-7, 2003

Merce Cunningham, Berkeley, February 7, 2003

John Cage, San Francisco, January 27, 2003

Charles and Lindsey Shere: homepage CS in Cadiz: photo: Eve Monrad |

Rome Opera, January 29, 2004 Edge Festival, Berkeley, June 5-7, 2003 Merce Cunningham, Berkeley, February 7, 2003 John Cage, San Francisco, January 27, 2003 |