A Flea in Her Ear: second-act scrimmage

Healdsburg, January 19, 2005—

In “the realm of the unreal”: art, biography, and cultural history

A FRIEND RIGHTLY chides me, without really meaning to, on my leaving him up in the air halfway through a visit, six weeks ago, to Glendale. Well, dammint, I think to myself, there’ve been extenuating interruptions, notably Christmas and all the pleasant family visits that entails, and then the New Year with its retrospect of regrets and memories and its forward glances toward a better use of what time remains.

We’ve been living in the middle of a train wreck, a collision between a particularly rich moment in private life and a particularly wrenching and alarming public one. By the latter I mean of course the election, the wars, and the inauguration. The friend whose casual inquiry about what may have happened next, after the Glendale trip in early December, suggested we all four go see a movie yesterday — at 10:45 in the morning! — and abandoning my two-week course in self-improvement, yes, a New Year’s Resolution, off we went. We’d never been to a movie in the morning before; it felt like a vacation.

Seeing this movie was a profoundly moving experience, first for the beauty and intelligence of the film itself, second for its relevance to the introspection that’s driven this new project of mine, third for having somehow brought together thoughts about theater, memory, the inner life, and the historical moment. So I urge any of you who think about these things to see In the Realms of the Unreal , a ninety-minute documentary by Jessica Yu about the life and work of the “outsider” artist Henry Darger.

Darger was born in Chicago, at about the time Modernism was, in the last decade of the 19th century. His mother died when he was four, and poverty forced his father had to give him up for adoption not long after. Considered a troubled child, he was remanded to a home for “feeble-minded” boys. He ran away at sixteen walking a hundred miles back to Chicago, where he found a job as janitor in a Catholic mission. For the rest of his fairly long life he lived alone in a rented room. Over the course of sixty years, quite unknown to anyone else in the world, living as a recluse in a room no one was permitted to enter, he painted hundreds of watercolors, nearly all of them to illustrate the book he was writing, a 15,000-page novel he called The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, as caused by the Child Slave Rebellion.

When Darger died in 1973 his landlord, Nathan Lerner, by happy coincidence a photographer, found this amazing life’s work. Lerner and his wife, the musician Kiyoko Lerner, are interviewed in Jessica Yu’s film. Most of the film, though, is an unseen narration, largely drawn from Darger’s journals and that amazing novel, illustrated by scans across his watercolors, frequently set in motion by a team of resourceful and respectful animators.

The film is about Darger, but also a cinematic version of the novel, which is a Surrealist masterpiece. It reminded me immediately of the work of Raymond Roussel, whose own dramatization of his novel Impressions d’Afrique inspired Marcel Duchamp — except that Roussel clearly wanted his work known by the public, he wanted to be an Important Author, and Darger, as far as I know, made no effort to publish his own work.

But what most seized my attention, watching this entrancing documentary, was its relevance to my own mood, very much turned inward as I approach my seventieth birthday; and to the last play we saw in Glendale, not yet written about here; and to the historical moment. To begin with the last: The Story of the Vivian Girls... is a war novel and more specifically a novel of insurrection. I’ve been reading Spanish history, at the moment Mar’a Rosa Menocal’s The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain . I’ve been reading this to prepare for our next trip: we leave in less than three weeks for another month in Spain, starting with a week in Madrid and then a further exploration of Andalusia. Menocal’s book is deceptively subtitled: that “culture of tolerance” was a brief moment in a long history of civil war — to use a phrase that’s always seemed to me an ironic oxymoron.

The peninsula we now call Spain and Portugal has been settled and sometimes actually administered, in turn, by Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Visigoths, “Moors,” Christians, and Fascists. The “culture of tolerance” lasted a few hundred years and was largely enabled, as I understand it, by a practical adjustment to theology: on the part of the intellectuals, by preferring literature and philosophy to religious doctrine as the fundamental organizing principle of one’s esthetic and intellectual life. (The part of the rest of the citizenry is not really addressed by Menocal, or by many other commentators come to think of it; but I imagine they put religious zeal second to the necessities and pleasures of daily life, as demanded or provided by the authorities of the moment.)

For about four hundred years Islam “governed” Spain’s cultural and intellectual life, and what was interesting was its accommodation of the religion of Islam, still quite new at the beginning of this history, and the inheritance of Hellenism. The branch of Islam that went to Spain was apparently exiled by the more zealous and “fundamentalist” Mohammedans who kept the Arab world for themselves. Who can doubt cultural and political similarities between that historical moment, twelve hundred years ago, and our own? And who of us doesn’t yearn for the peaceful accommodation of theological doctrine, economic stability, relative peace, and cultural refinement that characterized al-Andalus, whose capital, C—rdoba, was the largest city in Europe, and boasted the finest libraries of the age?

Menocal’s book is repetitious and badly edited, unfortunately, but suggestive and insinuating, like its subject. And one of its most interesting qualities is its insistence on Language as the motor of Culture and, especially, cultural tolerance and drift. She reveals this Andalusian civilization as the indispensable link between the ancient Greek poets and philosophers and historians and the soon-to-awaken European vernacular cultures of Chaucer, the troubadours, and Petrarch, Boccaccio and Dante.

But such a moment seems a historical accident. It was largely the result of one tenacious and inspired man, Abd al-Rahman, who fled Damascus when his family, the Umayyads, were massacred by the rival Abbasids, who wanted to reduce the then-new religion of Islam to a blind fundamentalist repetition of what they chose as its pure heart: not God, as He revealed himself, but Mohammed, the prophet who recorded those revelations. (And, of course, more particularly, the surviving family of Mohammed, who the Abbasids counted as their own source of authority.)

Glendale, December 3, 2004—

Just fun for a while

WE’RE DOWN IN AN Econo Lodge on E. Colorado Street for one of our semi-annual theater fixes at A Noise Within, a theater company consistently good enough to drag us down to LaLaLand.

This week it’s two comedies and an unknown: Georges Feydau’s A Flea in Her Ear, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming. The Feydau was fabulous. I’ve seen it before a couple of times, I don’t recall where, never better than this. I think “A Noise Within” is at its best with crackpot comedy — it was with a production of Noël Coward’s Private Lives that they first seduced us, four or five years ago — and A Flea in Her Ear is nothing if not screwball. A Parisienne suspects her husband of philandering, and gets a friend to write a letter inviting an assignation in a dubious hotel. She herself goes, of course, to catch him. Before the resolution, a hilarious evening later, the stage is littered with a Spaniard, a drunk Englishman, a youth with a speech defect (hee heeheh is how he pronounces it, and virtually every speech he gives is so pronounced), an absurd ex-soldier turned innkeeper, a toady flunky who is the twin to the innocent husband, and so on and so on.

These people run in and out of doorways, disappear into secret rooms, turn up at inopportune times, and constantly get into one another’s hair. Hardly any of them speaks normally. Costumes, make-up, attitudes, and vocal delivery are full of tics and absurdities, all of them consistent. Nothing is sacred, and political correctness is a foreign concept. The large cast was remarkably consistent; the direction was keen and attentive; the sets were evocative and detailed. It couldn’t have been better.

A Flea in Her Ear: second-act scrimmage

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, on the other hand, came up short — precisely because it was directed in the same mode, by the same team. Lines were rushed; the distinctions of tone among the levels of the cast were not observed; Shakespeare’s poetry was largely ignored. The play within the play — the “rude mechanicals’” prodution of Pyramus and Thisbe — was by far the best thing in the production, and very good indeed. But A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a hell of a lot more than Pyramus and Thisbe.

No big disappointment; it was worth its admission. I don’t know how many times we’ve seen this play, in productions ranging from a fabulous Edwardian production at Berkeley Rep, probably twenty-five years ago by now, to an enchanting production in someone’s back yard in Oakland, with the audience moving to change perspective on the garden, gradually growing darker as the summer evening advanced, and the final apology spoken from an upstairs window looking out over the audience and the garden.

Even when the lines are rushed and bruised, as they were too often this time, Shakespeare’s poetry is so fragrant, and his observation so penetrating and accurate, that this play always affects me with a unique combination of power and insidiousness. And as magical and romantic as it is, it is also so intelligent, and so good-hearted. Nobles, the upper class, “mechanicals,” and fairies — representing the purely animal components so often directing us in spite of our reason and our discipline — all interact in a choreography at once balanced and dynamic. Here in Glendale this week the cast was enough to keep all this alive in spite of the direction, and I wasn’t sorry to have seen it.

WE HAVEN’T BEEN EATING this week with our customary discernment, by which I mean we’ve been minding the budget, at least a little. The one exception was yesterday’s dinner at Tre Venezie, about which I’ve written previously — it’s become a favorite of ours, an intimate, quiet, understated restaurant seating no more than forty or so on a quiet side street in Pasadena.

The name refers to the three regions making up Italy’s Veneto, the source and inspiration on which the chef draws: Friuli, the Alto Adige, and the Veneto itself. As a result this Italian restaurant does not always, or even often, seem “Italian.” Many of the dishes seem very Austrian; others veer off further east toward Slavic regimes. Eating here makes me want to explore northeastern Italy more than we have, and to spend a week or so in Trieste sometime soon.

We ate lightly, sharing a Russian salad, each going on to a pasta course, then having dessert. The salad reminded us of Piemonte, where Russian salad is still a standard. It’s an old-fashioned thing, I suppose: cooked vegetables — finely chopped carrot, peas, perhaps small bits of pepper, potatoes, all bound in a mayonnaise. Tre Venezie adds bits of pickled cucumber, adding crunch and piquancy; and nestles it in leaves of lettuce and sets it on a slice of fine prosciutto, and dresses it with a lovely green olive oil.

Lindsey had tagliarini (Piemonte again!) with porcini and shiitake, which seem disconcertingly unItalian to me but pleased her. My ravioli were more authentic, I thought; interesting for the texture of the pasta, made I believe with farro flour; and deeply flavored with porcini and scraps of lamb which I could swear had been braised with a tiny bit of orange zest. Both pastas were house-made, and cooked to exactly the right degree of tooth.

With this we had a half-liter of Valpolicella, a good hearty one but suave; and for dessert Lindsey had a thin slice of “Opera,” that deeply flavored chocolate tart, while I had a fabulous moscarpone with just a tiny bit of honey — and a small glass of house-made juniper-and-sugar digestivo. Tre Venezie is not inexpensive, but it is thoughtful, evocative, subtle, and immensely satisfying — which may have made A Midsummer Night’s Dream suffer by contrast.

Lindsey in Dan McCleary’s show at the Carl Berg Gallery

THIS AFTERNOON WE SAW a fine gallery exhibition of recent paintings by Dan McCleary, a painter we’ve known and loved for many years now. The Carl Berg Gallery, on Wilshire Blvd. near the L.A. County Museum of Art, is small, pristine without sterility, marvelously lit; and no paintings could have made it look better than these new ones of Dan’s. The first thing I thought of when stepping into the gallery was Gordon Cook, the masterful and rather neglected San Francisco painter: Dan’s work shares Cook’s rare combination of intensity and tranquility.

I see I need to explain that a bit. The paintings are intense because they require, and result from, an unflinching commitment to a searching kind of vision. They demand the viewer do more than glance: they require steady gaze, onto and into the surface, the subject, the mood, the moment. The intensity of this demand is an ethical statement: the painter and his subjects don’t slacken or stumble, and the viewer better not either.

But the paintings are tranquil — perhaps “serene” is a better word — because through this demanding exercise they arrive at a totally objective statement. The men and women in these paintings are seen at dramatic moments, but the drama is contained. There’s an equipoise in McCleary’s work, a dynamic balance — there’s that concept again — of motivation and intent, of action and repose, of being and expression. And of other things too, among them of representational accuracy and painterly freedom, for these are not photorealist paintings. They are equivalents, and I recognize the audacity of thinking this, of Vermeers, though perhaps more modest.

They were not injured by comparison with the impressive paintings from the Phillips Collection, which we saw next, at LACMA — chief among them the Renoir Boating party luncheon, the large Bonnard Palms, an impressive late Matisse interior, and some first-rate Manets, Degas, and van Goghs. These are all known quantities, of course, old friends, you might say. McCleary’s paintings (and I don’t mean to minimize his drawings and prints, also seen today) are also known, at least to us; but I find their continued evolution and the lasting impact of their subtle visual narratives more exciting. I’m tremendously glad to have seen them.

Rome, Nov. 6—

WE SAT OUT THE ELECTION here in Rome, after spending a week in Torino at the Salone del Gusto and another week recuperating from all that food and drink at I Mandorli and Verona, visiting with friends.

Now we have two weeks to revisit this city, again with the emerging American empire at the back of our minds as we consider the monuments to the failed Roman one of two millenia ago.

I am sending my usual e-mail dispatches to friends, reporting on what we find and what we think about it. You can read them here.

Healdsburg, Oct. 3—

WHILE RUMORS of a universal draft simmer, and Frank Rich writes chillingly of President Bush’s Messianic tendencies in today’s New York Times (‘Now on DVD: The Passion of the Bush’: you really gotta read this one), we continue to dance on the decks. Thursday we drove up to Truckee for dinner and conversation with an aunt, and Friday we drove home, stopping in Sacramento for more conversation with my great-aunt, 103 years old and bright and attentive, with little good to say about the political situation. (Unlike my unreconstructed aunt, who’ll never understand liberals.)

Lunch today out at Bodega Bay at a place Gaye and John raved about, the Seaweed Cafe. Not the most auspicious building: a sort of smalltown shoppingplaza; you park right in front and saunter into what was apparently at one time a bakery. Inside, an open kitchen on the right, a few tables seating perhaps twenty-six at most.

But, oh, the food! The menu made ordering difficult — clearly this is a place for regulars; you want to return over and over to try these dishes. We began by sharing two starters: a dish of sardines cooked on tomatoes and served au gratin, bracing and substantial; and a marvelous composed salad with sliced green and red tomatoes, cod rillette, a fig stuffed with tapenade, and an oyster on the half shell with salmon eggs, dressed with very good olive oil and a spray of dill.

Lindsey can’t resist salmon. This one was steamed in a cedar box, imparting a very delicate flavor, and accompanied by a carrot and broccoli in two colors. It reminded me of salmon eaten long ago at Mukamuk, a north coast Indian restaurant in Vancouver, where the salmon was probably cooked on a cedar plank — except that this was very delicate in both flavor and texture.

I had an absolutely fabulous thing, a variation of cassoulet, though not nearly as long-cooked: fresh shell beans, clams in their shells, and slices of duck sausage, in a redolent juice. I’d happily eat it twice a week for the rest of my life.

For dessert, a rich, deep, perfectly textured chocolate cake, with crystallized lemon zest, and bits of candied burdock and a squiggle of caramel.

The chef is Jackie Martine, a strawberry-blonde Bretonne who knows the secrets of scents, textures, flavor, and subtlety; and her partner is Melinda Montanye, who runs the house with verve and style. Together they market locally, gathering salt upcoast, finding produce in neighboring market gardens, and stocking only wines coming from west of Highway 101.

They have a good website:www.seaweedcafe.com. This is currently my very favorite California restaurant north of San Francisco.

The irreducible truth is that the invasion of Iraq was the worst blunder, the most staggering miscarriage of judgment, the most fateful, egregious, deceitful abuse of power in the history of American foreign policy. If you don’t believe it yet, just keep watching. Apologists strain to dismiss parallels with Vietnam, but the similarities are stunning. In every action our soldiers kill innocent civilians, and in every other action apparent innocents kill our soldiers—and there’s never any way to sort them out.and

This isn’t your conventional election, the usual dim-witted, media-managed Mister America contest where candidates vie for charm and style points and hire image coaches to help them act more confident and presidential. This is a referendum on what is arguably the most dismal performance by any incumbent president—and inarguably the biggest mistake. This is a referendum on George W. Bush, arguably the worst thing that has happened to the United States of America since the invention of the cathode ray tube.

All it takes to make a Bush conservative is a few slogans from talk radio and pickup truck bumpers, a sneer at "liberals" and maybe a name-dropping nod to Edmund Burke or John Locke, whom most of them have never read. Sheep and sheep only could be herded by a ludicrous but not harmless cretin like Rush Limbaugh,…

I don’t think it’s accurate to describe America as polarized between Democrats and Republicans, or between liberals and conservatives. It’s polarized between the people who believe George Bush and the people who do not. Thanks to some contested ballots in a state governed by the president’s brother, a once-proud country has been delivered into the hands of liars, thugs, bullies, fanatics and thieves. The world pities or despises us, even as it fears us. What this election will test is the power of money and media to fool us, to obscure the truth and alter the obvious, to hide a great crime against the public trust under a blood-soaked flag. The most lavishly funded, most cynical, most sophisticated political campaign in human history will be out trolling for fools. I pray to God it doesn’t catch you.

"will be lifted out of their clothes and transported to heaven where, seated next to the right hand of God, they will watch their political and religious opponents suffer plagues of boils, sores, locusts and frogs during the several years of tribulation which follow."

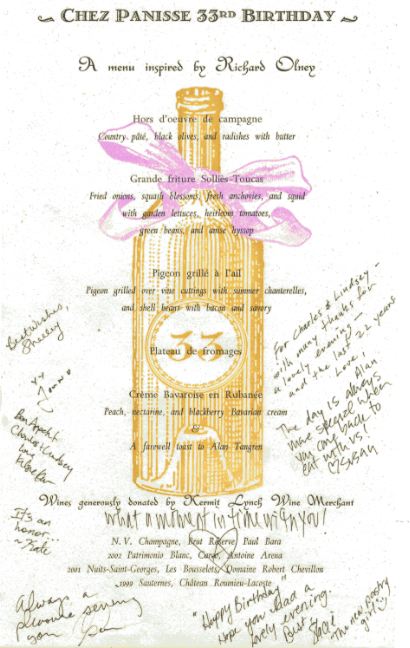

| Healdsburg, Aug. 29— A Third of a Century WELL, NOT QUITE. That has to wait until Christmas. But yesterday was the thirty-third birthday of Chez Panisse, a time to pause, reflect a little, and celebrate. |

|

Healdsburg, Aug. 9— Picking Blackberries

They come hot and heavy, literally, the wild blackberries, in these Sonoma county summers. They won’t hold much longer: the days are heating up. Maybe one more pass at them is all we’re likely to have.

Picking blackberries is an exercise in critical thinking: it involves choosing. Some are ripe. A few are overripe. Most are underripe and will have to wait for the next pass.

Of course by then hot weather may have fried them on the vine and it will be too late. Already the best berries are those inside the foliage, shaded from the sun and protected from the drying winds. And, of course, I’ve forgotten to bring my secateurs, and my gloves.

It’s an exercise in critical thinking, but it’s mindless work; the critical decisions are mostly intuitive. If I think of anything I think of Blank Road, 1950 or so, when the whole family would go to the blackberry patch halfway down our dirt road, nearly a mile long, with milk buckets and tobacco cans and boxes and such, to pick berries until the light began to fail.

I think of that, and then I think of the Democratic convention that we watched a week or so ago.

Two attitudes are contending for supremacy, not only in the November election, but in the consequent prevailing attitude of the American experience.

They are, put most simply, maturity and immaturity.

This is the only way I can understand the prevailing meanness, arrogance, and opportunism of so much of the extreme right wing. No matter where you look — the environment, business practice, international relations, tax policy, even the arts and entertainment — the prevailing attitude seems designed to appeal to the instincts and values of a fourteen-year-old boy. (I apologize to my grandson, who just turned fifteen.)

This comes to mind while picking blackberries, perhaps because I am reading — though not while I pick — a book by Wendell Berry, Life is a Miracle (Washington: Counterpoint, 2000). The book jumped off the shelf at the Sebastopol Library, but I will have to buy a copy, and maybe another for lending, it’s that good. The title’s from King Lear: Gloucester, blinded, thinks he has jumped off a cliff and killed himself, and is chagrined to have survived, and begs the stranger who has helped him (in fact his long-exiled son Edgar)

Away, and let me die.Edgar compliments the old man on his survival, assuring him he’d fallen the length of ten ship’s masts.

Thy life’s a miracle. Speak yet again.

Cloning… is not a way to improve sheep. On the contrary, it is a way to stall the sheep’s lineage and make it unimprovable. No true breeder could consent to it, for true breeders have their farm and their market in mind, and always are trying to breed a better sheep. Cloning, besides being a new method of sheep-stealing, is only a pathetic attempt to make sheep predictable. But this is an affront to reality. As any shepherd would know, the scientist who thinks he has made sheep predictable has only made himself eligible to be outsmarted. [Berry, Life is a Miracle, p. 7]

The hard and binding requirement that freedom must answer, if it is to last, or if in any meaningful sense it is to exist, is that of responsibility. For a long time the originators and innovators of the two cultures [science and the humanities] have made extravagant use of freedom, and in the process have built up a large debt to responsibility, little of which has been paid, and for most of which there is not even a promissory note.

The debt can be paid only by thought, work, deference, and affection given to the integrity of our ecological and cultural life. [Ibid., p. 73]

It is easy for me to imagine that the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines. [Ibid., p. 55]

Healdsburg, August 6—

Home again, and glad to be. But still thinking of…

Lunch chez Leedy

What is there to be said about a perfect lunch, prepared with intelligence and love by a dear friend? Here you have eggplant, zucchini, little white beans, home-made ricotta, and fried zucchini blossoms on a bed of romaine leaves — every bit of it from the garden. (Well, maybe not the beans. I’m not sure about them.)

It was all grown in a modest back yard in Corvallis, Oregon, and harvested with gratitude and enjoyment, and cooked with scholarship and acumen, and served with generosity and enthusiasm,

by one of the most thoughtful, reasoned, and fascinating men I know.

untitled

I don’t read newspapers very carefully, or follow the political discussions as a general rule. I make exceptions to this at certain times, and the presidential election is one of those times. We’ve been watching the convention the last few nights, as best we can here, via CNN, whose instant analysis drives me nuts. I don’t know which is my major response to the event, my admiration for many of the speeches we’ve heard or my contempt for the caliber of the intelligence commenting on them.

I have to say that for the first time since September 11, 2001, I’m a little optimistic about the future of this country. The optimism set in after watching “Fahrenheit 9/11,” which I hadn’t expected to admire at all. It was clear, watching this, that if that movie is seen by enough “swing” voters — not to mention those who generally don’t vote — it might be possible to outvote the manipulations of the Bush backers.

And the speeches in Boston have continued this optimism. I thought Mrs. Kerry, Al Sharpton, and Barack Obama were eloquent, truthful, and sympathetic; and Senators Kennedy and Edwards did no real harm to their own cause. We just watched Kerry’s speech, and thought it was pretty good too, though of course I’m still waiting for a more specific discussion of the kinds of points I raised here a few weeks ago. (See below, July 9)

But there’s time for that; that’s what the next three months are for. I’m pleased that Kerry and the Democratic Party have been listening to opposition voices, from within the party as well as without — Dean and Sharpton, but Republican critics as well. Kerry is showing that “flip-flopping” is in fact hearing disagreement, examining his own stand to see if it needs adjustment. He corrects his course as he goes, as we all must.

But I must say I am troubled by two constants in this political season. One, of course, is the shocking meanness of so many Republicans: their unconcern for the plight of “their own people,” to use the phrase that’s always thrown against Saddam Hussein. There was an article in the Sunday New York Times magazine about the calculated campaign launched by this wing of the Republican Party a few years ago. Fortunately a few intelligent people have noticed this, analyzed it, and begun the work to counter and overcome it.

The other is the constant trivializing by the press of this entire business, this public activity that is contemporary politics. The serious threats are minimized or ignored or even marginalized; such minor issues as physical appearance and pastime are given disproportionate attention; and style is nearly always set above substance. Worst of all, commentators — certainly on CNN — respond to everything in terms of adversary analysis, seeing the campaign as a game between two opposed teams, rather than the profound national discussion of public policy that it is.

This infects more than simply their “coverage,” I’m afraid: it reinforces the American tendency to simplify issues, to interpret complex issues in terms of good guys and bad guys. The recent history has shown that the manipulable majority prefers simplicity to complexity, and that does not bode well for intelligent policy. But how strange to see journalists and commentators falling into the same lazy way of thinking!

Portland, July 27 —

EVERY YEAR LATELY WE’VE SPENT A WEEK in Ashland with three other couples in a nice old house an easy walk from the theaters. Ashland is famous for its theater; its Shakespeare Festival is one of the most significant repertory companies in the world. We’re lucky to have the opportunity to see so much theater in so short a time, and to discuss it with so many good friends, and it’s worth the time, drive, and — let’s face it — expense.

There are a number of reasons the theater is so good. First, the repertory: centering on Shakespeare, but setting against him other plays, contemporary and not, American and not, with the inevitable result of making Shakespeare even bigger, even more profound and relevant.

Then there are the physical productions: either complex or stunning or both, some in the outdoors “Elizabethan” theater which suggests Shakespeare’s Globe, others indoors in the big but acoustically fine Bowmer Theater or the new black-box New Theater with its flexible audience seating — in the round, or deeply thrust, or “alley,” with the audience on both sides of the players.

The sets, costumes, and lighting are almost uniformly successful — enterprising, substantial, well-financed, technically quite up to the other standards. The directing is usually serious and thoughtful, whether conventional or (as is sometimes the case) quite “against the grain.” And the acting is quite marvelous: these actors are of the highest caliber, and the long rehearsal and longer season enables precision and depth in the ensemble.

This week we saw no fewer than five Shakespeare plays — six, in fact, though the second and third parts of Henry the Sixth were combined in a single evening. And, for me at least, Shakespeare quite dominated the week, with a gripping performance of King Lear, fine productions of the Henry VI plays, and a breathtakingly sparkling staging of A Comedy of Errors.

(At Ashland last week the term “bling bling” came into my consciousness, belatedly I suppose; I can’t think of a better application of the phrase than to this production.)

WHAT WAS IMPRESSIVE ABOUT ALL THESE PLAYS was the extent to which they were History. Ashland has a very sensible approach to Shakespeare’s History Plays, doing them in cycles chronological with respect to their subjects, with consistently cast actors where possible. Last year the cycle began with Richard II; this year it continues through the War of the Roses; next year we meet Richard III. But the tragedies, and even the comedies, enlarge the historicity of these histories, revealing endless layers of detail about the time and place of Shakespeare’s actions, and thereby the timelessness and universality of the human conditions they portray.

So A Comedy of Errors, though its director had set it in today’s Las Vegas, worked perfectly well. Ephesus (and Antioch and Smyrna and I suppose Constantinople) were the Las Vegases of their time, or at least the time that Shakespeare suggests — combining luxury and squalor with that peculiar tastelessness that inevitably results from wretched excess. Merchants and con artists, whores and gangsters, and the occasional sympathetic nice guy from every quarter, with every outlandish local accent and absurd detail of clothing — these were no doubt as common in Rome and Byzantium two thousand years ago as they are in Las Vegas and Miami Beach today.

And that insight enlarges one’s study, in these productions, of the dark ages of Lear’s legendary monarchy; and the brutal arrogance of medieval England. (Whose imperious occupation of its own island as well as France might serve as warning to contemporary globemasters.)

Around this Shakesperian center we saw arranged, last week, Charlotte Jones’s Humble Boy, Lorraine Hansbury’s A Raisin in the Sun, and The Royal Family, a badly dated piece by Edna Ferber and Moss Hart. The first two continued the enlargement of Shakespeare’s points, with Humble Boy examining the distancing and ultimate reconciliation among family members unable at first to accommodate one another’s needs — surely a subject with universal political overtones as well as psychological relevance — and A Raisin in the Sun still full of vitality and poignancy in its insistence on dignity and humanity in the face of societal injustice.

Only The Royal Family and, for me at least, Much Ado About Nothing seemed to fall short of the highest theatrical values last week — the former because of its book, and in spite of its direction and acting; the latter because of its direction but perhaps also partly for its book, surely not Shakespeare’s most inspired writing.

WE HAD MADE AN EARLIER TRIP to Ashland, nearly two months ago, with our Dutch friends Hans and Anneke, with whom we’d seen the first part of Henry VI — fascinating to have the chance to see it twice, and see the difference six weeks had made in it. (It was neither “better” nor “worse,” merely a slight bit different, and that perhaps more owing to our greater familiarity than to the ripening of ensemble give-and-take.)

And a few weeks ago we drove up to Ashland just for a day, believe it or not, to see two plays which had dropped from the repertory by the time of last week’s visit. They were as fine as anything we saw last week, or nearly so: Friedrich Durrenmatt’s The Visit, about the cynical and powerful punishment wrought on the small-minded and failed Swiss town of her abused childhood by a woman grown wealthy and manipulative by her own ethical compromises; and Suzan-Lori Parks’s Topdog/Underdog, both hilarious and tragic in its view of hopelessness in today’s Harlem.

All these plays — their writing and their performances — examine the huge problems facing us today: political, societal, familial, personal. It’s a cliché, I know, but they prove the significance, the relevance, even perhaps the possible transcendance of Theater, to which humanity has always turned at critical moments when examination of the human condition seems most crucial. No one that I know of does it better, more consistently, more wide-rangingly, than Ashland.